In honor of the University’s 125th anniversary, we offer an in-depth chronicle of the life and legacy of founder John Simmons (1796–1870).

For University Archivist Kelsey Kolbet ’21MS/MA, Simmons’ signature curriculum transforms students into scholars and practitioners. “Simmons is very unique in that it has both an academic and practical orientation. You are trained in theory, while also getting hands-on, professional training.”

This commitment to an intellectual and pragmatic model of learning is enshrined in Article 16 of founder John Simmons’ bequest: “It is my will to found and endow an institution to be called Simmons Female College, for the purpose of teaching medicine, music, drawing, designing, telegraphy, and other branches of art, science, and industry best calculated to enable the scholars [i.e., students] to acquire an independent livelihood.”

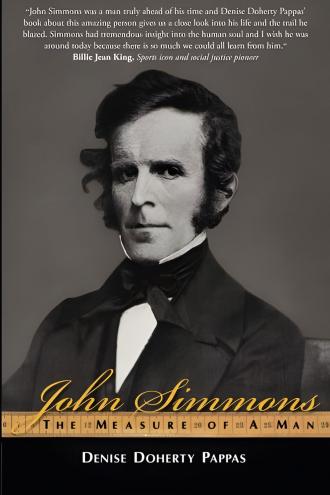

In her biography of the University’s founder, John Simmons: The Measure of a Man, Denise Doherty Pappas ’71, ’85MBA writes, “From its inception, Simmons classes prepared women for the labor force and for self-discovery.”

Makings of a Merchant Prince

Eventually known as the “Merchant Prince of Boston,” John Simmons’ (1796–1870) family lineage is traceable back to 1611. His ancestors were English Pilgrims who relocated to Holland, and subsequently to colonial America. On November 19, 1621, John Simmons’ great-great-great-great-grandfather, Moses Symonson (the surname became Simmons by 1633), boarded a ship called Fortune that was destined for Plymouth, Massachusetts. (The historic Mayflower had arrived one year earlier). Thus began the American branch of the Simmons family.

Over several generations, the Simmons family acquired land and worked as proprietors, farmers, and shipbuilders. In 1684, they settled in Little Compton, Rhode Island. John Simmons’ father, Bennoni Simmons (1775–1835), fought in the Revolutionary War, including the Battle of Bunker Hill. Despite having his arm forcibly amputated by an English cannon, Bennoni eventually returned to his ship carpentry trade, still more physically dexterous than most of his fellow tradesmen.

The sixth of eight children, John Simmons was born in Little Compton on October 30, 1796. In his late teens, he relocated to Boston to explore the city’s burgeoning commercial opportunities. There he began work as an apprentice in the tailor shop of his older brother, Cornelius Simmons (1785–1822). John Simmons spent his early adulthood learning and mastering his trade, all the while becoming astutely aware of his customers’ needs. At age 22, he opened his own tailor shop and became one of America’s most successful clothing manufacturers.

John Simmons’ shop received commendable reviews. According to an 1848 pamphlet entitled The Stranger’s Guide to the City of Boston, “Mr. Simmons … employs none but the most skilled cutters, and the organization of his establishment, the fairness of his team, and the fidelity with which his garments are made up speak volumes in his favor.”

In 1818, Simmons married Ann Small (1797–1861) of Provincetown, Massachusetts. They had six children, though only two of them — Mary Ann and Alvina — outlived their father. By all accounts, Mr. and Mrs. Simmons adored each other and their children were spirited.

Music was a beloved pastime for the Simmons family. Alvina possessed a music book filled with waltzes and quick steps, while son John Jr.’s flute remains extant. Mary Ann traveled the world and collected works of art with her second husband, William Arnold Buffum. Part of this collection now belongs to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, including an Etruscan bronze bracelet, an “archaeological revival style" amber necklace, and numerous other adornments, decorative objects, devotional figurines, and game pieces.

As John Simmons’ fortune grew, the family moved to more fashionable Boston neighborhoods. In 1841, he acquired his so-called mansion property, located on 133 Tremont Street, next to The Cathedral Church of St. Paul. During the latter part of his career, Simmons also invested in real estate, expanding further his fortune.

Simmons’ most significant contribution to cloth manufacturing was innovating the “ready-made” suit for men (more generally known today as prêt-à-porter or ready-to-wear garments). Over time, he realized that many individuals wore similar sizes, so he devised a way to capitalize on this pattern. Differing from the customized tailor-made suits — which were time-consuming and expensive — and appearing decades before the development of the sewing machine, these new garments could be produced more efficiently and cost-effectively. The production process entailed cutting segments of cloth in Simmons’ shop, then sending the pieces out to be stitched by skilled “needlewomen” (female sewers) in their homes. Lastly, the stitched pieces were returned to the shop (which included male employees) for finishing and pressing.

Simmons’ method, which made suits available at a lower cost to consumers, revolutionized the creation of men’s clothing. According to Pappas, clothing played a pivotal role in social mobility for mid-nineteenth-century Americans. “The self-made man was now to be admired, not scorned,” she writes.

In concert with Pappas’ analysis, Kolbet’s favorite object from the University Archives is one of John Simmons’ surviving looms. This object “not only tells the story of John Simmons and how we got here … [it] also tells us about his democratization of clothing and the democratization of women’s education,” she says.

A Complicated Legacy

Beyond his aptitude for the clothing trade, diverse socioeconomic shifts facilitated John Simmons’ professional success. During his lifetime, the expansion of the railroads, the Industrial Revolution, waves of immigration, and the rise of the middle class helped secure the viability of his commercial endeavors.

There is, however, an unsettling side to the New England textile industry. In her 2024 Founder’s Day presentation, Kolbet explained how the increased demand for cloth in the North depended upon enslaved labor in the antebellum South, specifically within the cotton industry. “As we [celebrate 125 years of this great institution] … we must also acknowledge the social and economic systems in which John Simmons made his fortune,” she said.

In addition to enslavement, the textile business contributed to the stratification and gendering of labor in nineteenth-century America. Pappas chronicles how John Simmons employed hundreds of needlewomen, often from Roxbury or the South End, as well as widows of military veterans and farmers’ wives residing in more rural areas. In 1814, Francis C. Lowell developed the first cotton mills in nearby Waltham, Massachusetts. The “mill girls” Lowell employed were typically young, unmarried female immigrants with few communal or educational resources. The mill girls and many needlewomen endured 12-hour workdays for low wages. Thus, Simmons’ impressive fortune was complicit in the exploitation of laborers, both free and enslaved.

Paradoxically, Simmons also immersed himself in a progressive cultural milieu. According to Kolbet, he was most likely a member of the Whig party, which had abolitionist leanings. He was a devoted member of the Brattle Square Church, a liberal Unitarian community that performed acts of charity for the poor. As Pappas explains, the Unitarian denomination complemented strands of Transcendentalism along with the so-called Protestant work ethic, all of which embraced a more idealized, optimistic view of humanity and championed humankind’s capacity to embody goodness through education, equitable labor, and democratic participation. Pappas condenses these influences on Simmons: “His religion encouraged social reforms with these answers: abolition, education, economic justice, and compassionate care.”

Despite his meteoric rise in status, John Simmons did not extravagantly flaunt his wealth. He enjoyed the simple pleasures of hunting, fishing, and eating johnnycakes (cornmeal pancakes with Indigenous Algonquin origins). The late Professor Emeritus of Chemistry Kenneth Lamartine Mark discussed John Simmons’ personal characteristics in his 1945 book, Delayed by Fire: Being the Early History of Simmons College (reprinted in 2018 by Forgotten Books). Mark conveyed how Simmons had a reputation for being shrewd, frugal, fair, and charitable.

On August 29, 1870, John Simmons passed away at the age of 73, due to complications with Bright’s Disease. He was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. (The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a distant relative of his, also rests there). An obituary published in The Boston Post commemorated Simmons as “eminently a self-made man, and his example can be studied with profit and interest by the rising generation.” The Boston Advertiser eulogized his many virtues: “Mr. Simmons … was genial in nature and fond of social intercourse but he seldom confided his plans to others. He was naturally a very kind-hearted man, and he performed many acts of charity … Unostentatious in all things … He was always straightforward and scrupulously just in his transactions, and when he made a friend, the friendship was a lasting one.” Pappas crisply summarizes his persona: “[John Simmons was] a man of ‘deeds, not words.’”

Simmons’ most enduring legacy, however, is the institution of higher learning that he envisioned and endowed.

Philanthropic and Proto-feminist Leanings

Though John Simmons did not have any surviving male heirs, he made sure to provide for his daughters’ and granddaughters’ long-term needs when drafting his will. Unbeknownst to many of his relatives and associates during his lifetime, Simmons also made plans to endow Simmons Female College.

“[Back then], it was very novel to set aside this much money for women’s education,” says Kolbet. “John Simmons saw this as an opportunity to enable scholars [i.e., students] with an independent livelihood [after college], and this became his mission.”

Pappas notes that Simmons intended for the College to be tuition free. However, the Great Boston Fire of 1872 damaged many of Simmons’ uninsured properties that were supposed to generate income for Simmons Female College. (The fire also delayed the incorporation of the College by nearly three decades).

It proves difficult for historians to reconstruct John Simmons’ motivations for creating a women’s college. Although the University Archives possesses the John Simmons Papers and the Simmons Family Papers, the founder left no direct testimony or diaries. (The City of Boston Archives and the Little Compton Historical Society house additional materials).

Pappas argues that Simmons desired to pay it forward, so to speak, to the needlewomen who helped make him so profitable. “This forthright clothing manufacturer saw with his own eyes the impoverished living conditions of many in his female workforce. Over time he observed their skills, recognized their talents, appreciated their work ethic, and learned of their personal hardships,” she writes.

Kolbet concurs: “John Simmons contracted a lot of labor out to women … he was very much aware of the social chasm between the women working for him and himself.” Furthermore, Kolbet observes that most women’s colleges were founded by women, and their curriculum tended to suit an upper-class (as opposed to working-class) student body. “Looking back … Simmons Female College was really revolutionary for its time.”

A Balanced Learning Model

Standing apart from other women’s colleges, the learning model espoused by Simmons Female College — renamed Simmons College in 1915 and Simmons University in 2018 — achieved an ideal balance between the liberal arts and career preparation. In Kolbet’s words, “Having that cross-disciplinary exposure is so important … You get this perspective of looking at the world as a whole rather than as parts. We are making sense of things in a more integrative way.” While pursuing graduate studies in Archives Management and History through the School of Library and Information Science, Kolbet appreciated the hands-on learning and internship opportunities that Simmons offered.

The institution’s delayed opening may have influenced its curriculum. The landscape of higher education and vocational training for women in New England underwent changes in the years between the death of John Simmons and the incorporation of the College. Dr. Henry Lefavour, the College’s first President (previously a chemistry professor and dean of Williams College) advocated for “specialized technical training” that would prepare female graduates for “remunerative labor.”

Lefavour understood that higher education needed to adapt to changing times. During an administrative meeting in 1901, he remarked that Simmons must “lead the way with standards of the future rather than of the past.” Lefavour’s connections brought in excellent STEM faculty from nearby Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A course catalog from the 1903–1904 academic year details course offerings within the College’s inaugural six schools: School of Household Economics, Secretarial School, Library School, School of Science, School of Horticulture, and School for Social Workers.

Speaking at the College’s opening ceremony on October 9, 1902, Lefavour proclaimed: “This college is unique, in that it is the first to stand in New England for a utilitarian education for [women], while aiming not to neglect any influence that may broaden the students’ outlooks and deepen their lives. What our idea may accomplish, however, will be determined by you young women.”

Education and Equity

From its inception, the College catered to students with limited resources. While tuition was not free (as John Simmons intended), in her essay on the history of working women’s education in Boston, former Professor of History Laurie Crumpacker ’63 demonstrated that tuition was kept modest and several needs-based scholarship funds were established during the early decades of the College. The location of the campus at 300 The Fenway was significant, as commuting students from Roxbury and the South End — the same neighborhoods where many of John Simmons’ poor needlewomen resided — could access the college more easily.

Equity is both a founding precept of the institution and an animating principle of its community. “The University never imposed a Jewish quota, even though many colleges back then did. This makes me proud to be a Simmons alumna,” Kolbet reflects.

Pappas describes the early cohorts of Simmons students as bold, independent, and avant-garde. Lydia Brown, Class of 1914, was Simmons’ first Black student, whereas Sarah Louise Arnold (1889–1954), the College’s first dean, was a prominent suffragist. Certain Simmons affiliates and their ancestors risked their lives to achieve equality. For instance, psychologist Dr. Helen Boulware Moore, an emerita faculty member and administrator, is the great-granddaughter of Robert Smalls (1839–1915), an enslaved African American man who bolstered the Union cause and liberated 17 Black passengers by intercepting and commandeering the Confederate gunship known as the Planter.

“The institution was very forward-thinking for its time and was always thinking outside the box concerning more conduits for equality,” Kolbet reflects. Unsurprisingly, Simmons students across the generations are celebrated for their activism, particularly on behalf of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ individuals. “People come here [to Simmons] … and they fight for social justice; that’s very much the lifeblood of the institution.”

John Simmons’ legacy symbolizes the transformative power of higher education. At the conclusion of her Founder’s Day presentation, Kolbet said, “It is through our actions [stemming from learning, social justice, advocacy, and resistance] that his legacy lives on.”