“While I am happy that there is a Black History Month, I think that Black history should be celebrated throughout the year, given the various intersections [of Black culture within human history],” says Patrick Sylvain, Assistant Professor of Humanities. An artist-scholar of Haitian and African American ancestry, he is acutely aware of cultural hybridity.

As one example of cultural crossroads, Sylvain recounts how his own ancestors left Philadelphia in 1822, when Haiti began providing citizenship to Black individuals. “At that time, African Americans [in the United States] were still considered subservient individuals, so many immigrated to Haiti for birthright citizenship,” he says. “Then after emancipation, White supremacists wanted to send Black people to Haiti or Liberia, rather than living alongside them.”

This prescriptive exodus also appears in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Thus, Haiti played a crucial role in the Fourteenth Amendment. (Passed in 1868, this constitutional amendment granted citizenship to all persons, including those formerly enslaved, who were born or naturalized in the United States).

“When you think of Black history, you need to think of the various intersections within broader historical narratives,” Sylvain says. “I would like Simmons to honor this, since we are all interconnected . . . The US is, and has always been, a creolized [i.e., mixed or hybridized] society. In other words, we cannot claim to be a pure, White, homogenous nation.”

In one of his Spring 2025 courses, “Gender and Power Dynamics in Caribbean Women’s Literature” (LTWR 223), Sylvain exposes Simmons students to racial and gendered varieties of hybridity. Readings include Patrica Powell’s The Pagoda: A Novel (Knopf, 1998), Jamaica Kincaid’s The Autobiography of My Mother (Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1997), Edwidge Danticat’s Claire of the Sea Light (Knopf, 2013).

“These novels are not simply ‘art for art’s sake’ . . . Students are reading great literature but they are also learning about history . . . Caribbean literary creations take them beyond the Western canon and while also enabling them to be in conversation with the Western canon,” he says. Moreover, thanks to Sylvain’s robust connections in the literary world, Simmons students will be able to meet some of these contemporary novelists (either in person or virtually).

Curiosity Unbound

“I am an extremely curious individual. And I say, proudly, that I am a nerd,” Sylvain declares. “Being curious also makes me a good teacher, since teaching always involves learning.”

Sylvain ultimately became a humanities professor because of his insatiable intellectual appetite and a series of coincidences. He began writing poetry at age 13. Shortly thereafter, he became fascinated by motors and engines and contemplated becoming an engineer. While a student at Cambridge Rindge and Latin Public High School, Sylvain gravitated toward the study of law and the US Constitution, becoming Vice President of the Law Club.

During his undergraduate studies at the University of Massachusetts-Boston, he took courses in political science, philosophy, and social psychology. “I wanted to understand why certain leaders became dictators, and why people followed dictators,” he recalls. “I also was very interested in the notion of having bodies of laws that constitute what it means to be a nation.”

Given his multilingual competencies (in Haitian Creole, French, Spanish, and English), Sylvain was recruited to teach at his own high school, which has a significant Haitian population. While serving in the Boston public school system and teaching creative writing, he earned graduate degrees in education, creative writing, and, eventually, a doctorate in English.

Along the way, Sylvain interacted with phenomenal scholars and poets, including Professor of Sociology Orlando Patterson at Harvard University and U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky at Boston University. While teaching as a graduate student, Sylvain became a five-time recipient of Harvard University’s Derek C. Bok Award for Excellence in Graduate Student Teaching of Undergraduates.

Leaving the security of the Boston public school system for a subsequent career in academia was “a risk,” Sylvain recalls. “But it turned out to be the best decision I ever made, because of the intellectual satisfaction.”

The Politics of Poetry

Writing poetry has been a lifelong passion for Sylvain, and this artistic practice informs his scholarship. During his childhood, he gave poetry readings in conjunction with Black History Month and Haitian Independence Day. In conjunction with the fall of Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier’s regime in the 1980s, Sylvain began to understand the political contours of spoken verse.

“I was already reading in public and using poetry to engage with politics . . . and the Haitian community was very receptive to this,” Sylvain recalls. “I realized that poetry was direct and impactful. It reached the psyche in a way that a play, short story, or folklore could not. There is an immediacy to poetry that is very powerful.” Consider the first stanza of his poem “Blood,” which appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of the literary journal Prairie Schooner:

I was born on an island

Christened by genocide.

Blood is absolute here,

not water. Blood is the rumor

of an invasion; a coup; a servant’s

illegitimate baby; the color of one’s skin;

or the national id card denied to thousands

of Dominicans with Haitian ancestry.

Blood is the currency here.

For Sylvain, part of poetry’s expressive potency involves its rhythmic and ritualistic patterns. With four musician brothers, Sylvain is deeply attuned to the interrelationship between poetry and music. While poets and lyricists today distinguish between poetry and lyric (i.e., verses meant to be sung), in Haitian history and other pre-modern cultures, poetry was essentially a song chanted in a ritual setting.

“If you look at the great lyricists of more recent times — Michael Jackson, Bob Marley, Alicia Keys, Beyoncé, and others — there is a precision in terms of metaphors and emotions. And there is a refrain that is repeated . . . A great song or poem draws you in through repetition,” Sylvain explains. For him, this emotional trigger is not just sentimental. Poetry creates political cohesion; it can rally people around a nationalist or democratic cause.

Eventually, Sylvain became a member of the Dark Room Collective, a society of Black writers that formed in 1988, one year after the passing of James Baldwin. Members (many of whom are also professors) included Tracy K. Smith, Kevin Young, Natasha Tretheway, John Keene, and other luminaries. “The Collective became just as important as the Harlem Renaissance,” Sylvain says. This community introduced him to a larger circle of prominent Black writers, including Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Gwendolyn Brooks. With these direct influences, Sylvain developed further his notion of poetry as a political discourse.

Critical theory constitutes another profound influence on Sylvain’s poetry and scholarship. He notes that many philosophers were former (or failed) poets who knew that poetry could harness the spirit of a nation. “I came to realize that to have a [poetic] voice, you need to understand theory. Theory establishes the framework of knowledge . . . you cannot innovate in poetry without knowing this continuum of thought,” he says.

In particular, Sylvain gravitates toward French theorists. “The history of Europe is a history of warfare. These people have been traumatized [or have inflicted trauma], and they are trying to understand their collective identity,” he explains. “As scholars, we are seeking the truth, even if it is uncomfortable . . . To be clear, there is no single, universal truth, but there are truths . . .And we must not manufacture or accept alternative or false truths.”

Rearticulating Leadership

“If we want to move toward a humane society, then leadership must be curative, and proper,” Sylvain says. “It cannot be egomaniacal and self-serving — that is not leadership.”

In a Spring 2024 course, “Leading with Letters” (LDR 101), Sylvain and his students studied different types of leadership by examining first-person accounts. “Some students wondered why we were reading Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson,” he recalls. “But you start to see their intentions from their own writings . . . Even if you disagree with Jefferson’s racial politics, you can’t simply cancel him out—you must try to comprehend his vision.”

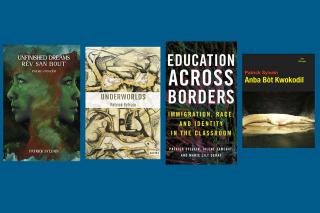

Leadership also comprises the subject matter of one of Sylvain’s forthcoming books, Scorched Pearl: A Critique of Haitian Leadership (Palgrave Macmillan, Fall 2025). “In this study of Haitian literature, I want to understand why Haiti became a so-called failed state . . . Despite having had a revolution [from 1791 to 1804], Haitians have not fully decolonized themselves,” he says.

Differing from past studies, he scrutinizes both internal (e.g., Haitian politicians) and external (e.g., Euro-American colonization) factors that affected the dynamics of leadership in Haiti. Drawing upon his background psychology, Sylvain probes dictatorial minds and egos. “In this ambitious project, I bring together the disciplines of psychology, political science, history, and literature to reconstruct the archetype of individuals who become dictators,” he says.

Zombification Offscreen

Sylvain’s second scholarly book project, Haiti and Being: Vodoun, Zombies and the Plantation Continuum, theorizes the zombie as both a historical figure with Caribbean roots and as a theoretical framing device. “Haitians fear the zombie . . . they have not capitalized on it like Americans have, making zombiedom into a multi-billion-dollar [entertainment] industry,” he says. Accordingly, this interdisciplinary study is in direct conversation with the Mexican transfeminist philosopher Sayak Valencia’s book, Gore Capitalism (MIT Press, 2018).

Sylvain demonstrates that the zombie embodies a powerful metaphor for race relations and dehumanization. Throughout the text, he coins varieties of zombification, including “cognitive zombification.” As he explains, “During slavery, education was disallowed . . . When you are not providing education to a particular group of people, like women and girls in Afghanistan today, that is a ‘cognitive zombification’ . . . The mind is supposed to be thinking and engaging critically all the time, so when you disable this, your will is removed, and you are stripped of your humanity and self-possession.”

Though Sylvain did not intend to investigate timely research topics, his revelatory approach helps us interpret the rise of oligarchic regimes in our contemporary moment. “Zombified minds prefer to have a very simple, linear narrative,” he explains. “Alternative truths are dangerous, because they bolster authoritarian leaders and sustain corrupt power structures.”

In this way, Sylvain’s scholarship, poetry, and teaching underscore the paramount importance of critical thinking. “I want my students to think about their own contradictions . . . We also need to disentangle the racialized aspects of our world, and become comfortable doing so,” he explains. “By understanding the complexities of Blackness and creolized cultures, we can understand the complexities of history and of the present.”