“The peer-reviewed article that I co-authored with my students was the first big research project that I shepherded from start to finish since coming to Simmons in 2018,” says Eric Luth, Associate Professor of Biology. “It’s a milestone for me and has a satisfying outcome.”

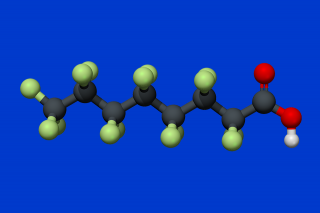

For this project, Luth and his students focused on a group of chemicals called polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which have been used in manufacturing to create fire, stain, and water-resistant surfaces. As past studies have demonstrated, exposure to PFAS is correlated with cancers, infertility, low birth weight, and delayed aspects of pubertal development in mammals. Luth and his team wanted to understand more about the causal relationship between exposure to these toxins and early development and growth abnormalities in C. elegans, a species of worm that is cellularly similar to humans.

“There is a high presence of these contaminants in the environment, mainly because they do not break down,” explains Luth. “They are nicknamed the ‘forever chemicals’ because once they get into the environment, they are very stable and do not biodegrade like other substances do. Since there are thousands of varieties of PFAS, we just tested two of the most common ones.”

One of the advantages of conducting experiments on worms is that they have a rapid generation cycle (3–4 days, as opposed to approximately 20 years for humans). “Since these worms develop quickly, we can easily track their growth,” says Luth. “What happens to them can be surprisingly good predictors as to what will happen to humans. In other words, if something is toxic to worms there is a good chance it will be toxic to mammals too, because our cells have a lot in common.”

The students conceptualized, developed, and executed all of the experiments related to this work. All of the data is student-generated, which is so wonderful.

The research team found that, at exposures to very high concentrations of PFAS, the worms grew and reproduced themselves at slower rates. The researchers also observed that individual worms with high exposure moved through their larval states more slowly. With extremely high concentrations of PFAS, the worms died.

While Luth administers caution when making any direct correlations between the demonstrated effects of exposure in worms and the presumed effects of exposure in humans, he considers this study a fruitful starting point for further research. “Many growth processes are shared between worms and humans, so it would be interesting for us to follow up on the various physiological and hormonal shifts that occur in response to these chemicals,” he says, expressing excitement about the genetic implications of subsequent research on PFAS. “We have lots of tools to tweak the expressions of genes, and we can target individual genes. My hope is to manipulate genes to make worms more sensitive or more resistant to PFAS. This would help us understand further the cellular processes that are affected by these chemicals.”

As Luth emphasizes, “The students conceptualized, developed, and executed all of the experiments related to this work. All of the data is student-generated, which is so wonderful. I mainly supervised throughout the process.” Luth’s lab (located in E280 of the newly renovated Lefavour Hall) now hosts several ongoing projects related to these chemicals, and he accepts second-semester first-year students through seniors — typically Biology, Neurobiology, or Biochemistry majors — to conduct laboratory research with him. Working together on these contaminants has also fostered opportunities for collaboration between different STEM departments at Simmons.

Kaitlyn Kessel ’23, who now works in the Fried Lab, a Neural Prosthetic Lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, joined the research project during her sophomore year. As a Biology major and Chemistry minor, Kessel was thrilled to gain some laboratory experience. In the process, she learned “how to plan accordingly, overcome obstacles, and even conduct my own experiments.”

The summer before her senior year, Kessel participated in SURPASs (Summer Undergraduate Research Program at Simmons), essentially a mentored and paid research experience for Simmons undergraduates. During that summer, Kessel took the research project in another direction. Together with Luth and other researchers, she transformed their research project into a publishable scientific paper.

“I was very new to the whole publishing process. I researched journals that would be appropriate venues for our paper,” recalls Kessel, who came to learn much about journal formatting, the peer review process, and turnaround times. “It made me realize how much hard work and time goes into each article I read and how each author on the article has put in so much time and effort.”

Luth stresses that being able to communicate your ideas clearly is essential for success in the sciences.

Good science is meaningless if you can’t communicate your ideas to other people. It takes being a good communicator to be a good scientist.

Luth believes that Simmons, with its strong spirit of collaboration, is a wonderful place for students to study STEM. “There is an interesting blend of opportunities and support in the sciences that we see here,” says Luth. “There is so much research transpiring on campus. In the new science center, we use the same equipment you would find at major research labs in Boston and beyond. It’s a great preparation for students going to graduate school or laboratory work, and we are seeing students taking advantage of these research opportunities even in their first year at Simmons.”

For Kessel, one of her favorite aspects of the collaborative research experience at Simmons was mentorship. “Professor Luth was an amazing mentor and I cannot thank him enough for what he and the entire Department of Biology have done. . . I was honored to be hired by a neuroscience lab right after graduation and it is because of the opportunities and the confidence that Professor Luth has given me.”

For his part, Luth encourages Simmons students to follow their interests. “Find something that makes you curious, and reach out to someone who is already doing this kind of research,” he advises. “It is never too early to get involved, and if you are passionate, this helps motivate you even when things get frustrating. We are always learning.”