“My degree at Simmons, and some people that I met at Simmons, were absolutely and completely influential in building up my confidence and my courage, and my sense of moral vision as I led into writing Wicked,” says Gregory Maguire '78MA, reflecting on the path to writing his best-selling novel, published in 1995.

Maguire was among the first graduates of the Master of Arts in Children’s Literature program at Simmons, now celebrating its 50th anniversary. One of the influential people he met during his studies was Betty Levin (d. 2022), a professor and founding faculty of the University’s Center for the Study of Children's Literature, whom he describes as, “a flinty, unsentimental New Englander.” Their friendship began when he was a student, and continued through the nine years he taught in the program.

Levin’s guidance proved especially pivotal for Maguire’s career when ReganBooks offered to publish his first adult novel, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. A reimagining of L. Frank Baum’s 1900 novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Maguire’s novel focuses on Elphaba, a green-skinned girl who would grow up to become the titular witch. In Maguire’s telling, Elphaba is a sympathetic character who is shunned for her skin color and passionately defends those marginalized in Oz society.

“My editor said, ‘We’re going to publish it, but you need to lose 5-8% of it, it’s just too long,’” says Maguire. At the time, he was staying with Levin in her farmhouse in Lincoln, Massachusetts, while speaking at schools across New England. “Betty said, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll do it.’ And we sat down with the manuscript of over 500 pages and we went through it page by page,” he says.

When the book was published in 1995, Maguire dedicated it to Levin. “Without her wisdom as a professor, a canny reader, an editor, and a writer herself, I wouldn’t have had access to the skillset that she had,” says Maguire. “I had a lot of imagination and a fluidity with language … but I didn’t know how to be restrained — some would say I still don’t! She knew how to cut out the malarkey.”

The Rise of Wicked

Upon its publication, Wicked was widely praised; Kirkus Reviews called it "A captivating, funny, and perceptive look at destiny, personal responsibility, and the not-always-clashing beliefs of faith and magic." It landed on national bestseller lists in 1995, and inspired the Broadway musical, which debuted in 2003. It was also the first novel in Maguire’s The Wicked Years series, followed by three other novels centered on his re-imagining of the Land of Oz. Wicked: The Graphic Novel Part I, illustrated by Scott Hampton, will be released in 2025.

Wicked: Part I was released in theaters in November, 2024. The movie, directed by Jon M. Chu, is based on the first act of the musical and will be followed by the sequel, Wicked: For Good, in November, 2025. The diverse casting choices featured across the film — most notably with Cynthia Erivo in the lead as Elphaba — have been praised by major news outlets as breakthroughs in diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Given the political undertones of the source material — Elphaba’s ostracization based on the color of her skin, and her staunch support of sentient animals in the face of their oppression — this accommodation with contemporary concerns makes a great deal of sense. By December, 2024, Wicked was number 1 on The New York Times Best Seller list, nearly 30 years after its initial publication.

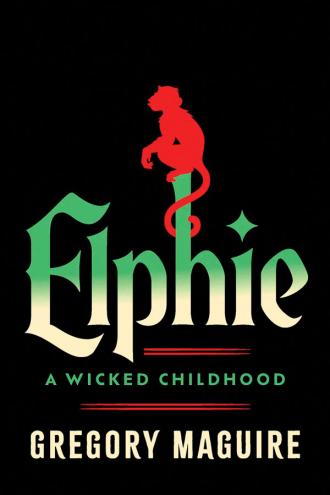

Meanwhile, Maguire has more to say about Elphaba. Before Wicked came to the big screen in 2024, he returned to some of the material he and Levin had discarded from his original draft.

“One of the things we took out was about four or seven pages about the life of Elphaba, who would become the Wicked Witch of the West, between the ages of 3 and 16. Who somebody is at the age of 7 and 11 and 14 is absolutely crucial to understanding how they got to be the person we begin to recognize,” he says.

Maguire’s forthcoming book, Elphie: A Wicked Childhood (William Morrow, March 2025) gives him the opportunity to fill in those gaps. “The truth is that I still care about Elphaba. She’s a person with individuality and with vitality still. She is part of me. I can still look at her and think, ‘I’m not quite sure how you operate, I know I never will, but there are still things to examine.’”

The Value of Literature for Children

More recently, Maguire has returned to children’s literature with Cress Watercress (Candlewick Press, 2022), a middle-grade fantasy featuring a young rabbit learning to cope after the disappearance of her father. The idea came to him while considering what type of story could be accessible to children while also giving them some insight into living with grief.

“The message I would like to give anybody in the third grade who is going to grow up to suffer — and who isn’t? — is that, yes, we can survive the bad feelings of the moment, but having survived them once doesn’t mean we’re done with them for good. What I think is missing from the emotional education of children is that life isn’t a series of episodes and hurdles and setbacks that you survive, it is a recurrence of emotional states, and the recurrence is natural. Emotional states come and go in a rhythmic pattern and knowing that you can survive them actually helps you survive them, but knowing that they will come back is also part of growing up,” he says.

In spite of the letters he has received from adults asking if he will write a sequel in which the rabbit’s father returns, Maguire insists that such expectations miss the point of the book. “The hope is that he will come back, because children are full of hope, but that’s not the challenge. The challenge is to accept that he will not come back, and that missing him is a lifelong state and it will lift and settle, lift and settle.”

Maguire notes that while people outside of the field may be dismissive of literature for children, the Simmons program fully embraces its value. “Children’s literature has a very specific job to do, and when it does it well, it changes lives. This is what Simmons taught me.”

In Maguire’s view, children’s literature requires greater skill. “Children have no patience with a piece of art that isn’t functioning now,” he says. “They will not wait three pages to see if it gets any better, if it’s not working they throw it on the floor and they go back to their video games.”

Adults, to their detriment, underestimate how “demanding and intelligent children readers can be, if you give them the right stuff,” says Maguire, noting that really good books “will captivate them, and will help them become better readers and, I believe, better citizens. All of that I got from Simmons.”

The Next 50 Years of Children’s Literature at Simmons

Reflecting on his time as a student, faculty member, and co-director of the Children’s Literature program at Simmons, Maguire sees a continued need for honesty in literature for children.

“It is important for Simmons to keep the windows cranked as wide open as possible to take in the wind of the current times without throwing into the trash the benefit of the past,” says Maguire. “We are a forward-looking nation and we believe in the future more than we trust in the past, but we have to do both. Children’s books … are a reflection of the world as it really is, and they must stay that way.”