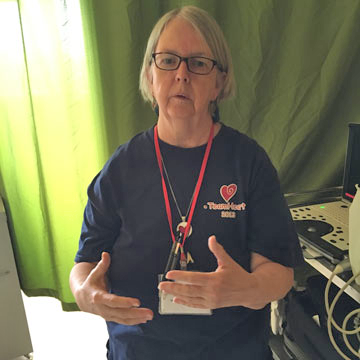

Before her recent retirement, Marilyn Riley ’73 spent 43 years in cardiac ultrasound. In 2010, while she was Director of Clinical Education Cardiac Ultrasound at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, she became involved with Team Heart, a nonprofit organization that provides much-needed cardiac care to patients in Rwanda. For eleven years, Riley took annual trips to Rwanda to support this effort. We talked to her about what this experience meant for her, and for her career.

“As an adult population, we don’t know much about rheumatic fever because we grew up with penicillin,” says Marilyn Riley ’73. “In the current medical climate, few Americans are aware of rheumatic fever anymore and its consequences because our medical system has limited the disease with antibiotics.”

Rheumatic fever, a complication of strep throat, can lead to heart valve issues later in life. Riley knew about the cardiac effects of the disease firsthand, having screened patients who had grown up in the Boston area before the advent of widespread antibiotics. “We screened 50-100 patients per trip, and selected 10-16 per year to undergo heart valve surgery replacement,” says Riley. “I knew how to image [perform a cardiac ultrasound] for this disease because of my Boston patients.”

Volunteering in Rwanda

This experience at Beth Israel made her uniquely prepared, years later, to volunteer for Team Heart, offering cardiac screening and surgery to people in Rwanda. Her mentor, Dr. Patricia Come, a cardiologist who knew Riley’s skillset and her interest in travel, sponsored her to travel to Rwanda with the team in 2010. For the next ten years, Riley continued to join these annual trips (eleven, in all) using her vacation time and paying her own airfare to Rwanda. The team of about 20 people included cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, nurse practitioners, ICU nurses, anesthesiologists, an Intensive Care Unit team and a post-operative care team.

The government of Rwanda supported the team by paying for hotel stays and one meal per day, and allowed them to take over one Intensive Care Unit and one Operating Room at a private hospital. “We were there for a ten-day surgical stretch,” says Riley. “We worked with local cardiologists and local internists who would alert us of who had problems.” Riley borrowed a portable ultrasound machine from Beth Israel and arrived with an ultrasound scanning partner a week before the surgical team, visiting the city and district hospitals to scan patients with cardiac issues. The full team would then select who was most in need of surgery. “At first, we would do maybe eight surgeries a year. Then up to about 16 [surgeries], once we had greater capacity and fluidity.”

Aside from the lack of access to penicillin to treat rheumatic fever, Rwanda suffered additional hardship to further impede access to treatment. “The country of Rwanda has about 10 million inhabitants,” says Riley. “At the time [2010] there were only four cardiologists in the country. The population of educated physicians was wiped out during the genocide [in 1994] — they had no cardiac surgeons in country. It was our mission not only to acutely support this population, but to train Rwandan nurses and physicians.” Now, there is a Rwandan-born surgeon, trained by Team Heart and educated in South Africa, performing cardiac surgery, as well as a fully trained surgical OR team. “Teaching was a major part of our mission. We had to help bridge those gaps to create a better health plan for these individuals.”

Team Heart was founded by Dr. R. Morton “Chip” Bolman, Chief of Cardiac Surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who saw the need for a surgical program in the wake of the 1994 genocide. “While internists and cardiologists were doing a good job of recognizing what was wrong with patients, once the scarring starts, there is no medical cure. It starts to obstruct the heart valves, and patients need open heart surgery for heart valve replacement. They needed cardiac surgeons,” says Riley. “[Team Heart] stepped into a void that existed, going to clinics and seeing what we could offer to help a patient population that was not yet able to be served by medical personnel in-country.”

The experience of a lifetime

From her first visit to Rwanda, Riley was fascinated by the countryside and the people. “In 2010, there were power outages every day, and no power to any housing outside of the city limits. I took pictures over the years, as the hillsides around the hospital started to light up as those neighborhoods got power.”

The team was careful to be respectful of the history of genocide and trauma that their Rwandan colleagues and patients had faced. “They were all about healing and going forward,” says Riley. “We loved working with them. They were grateful, warm, incredibly resilient, stoic individuals who won my heart.” She recalls patients who would wait patiently for hours — sometimes arriving the night before and sleeping on the lawn of the hospital — for their appointments, and children walking into town to fill cans with their water for the day. “It was my first experience [seeing] how much they did with how little they had. It was a very humbling, wonderful, joyful, heart-wrenching experience.”

The team was also able to visit one or more natural resources during each trip. “It was a huge privilege to see mountain gorillas in their natural environment — for me, that was an experience of a lifetime.” It gave her a valuable perspective when she returned to the high tech environment of one of the best medical centers in the U.S. “It made me so grateful to be in that environment and [be able to] serve people. I would come home and teach and share incredible stories with physicians and sonographers in training. This wasn’t just something that happened in February, [Rwanda] was with me all year, all the time.”

Gaining collaborative learning skills at Simmons

As for her original career intentions, the imaging field didn’t exist when Riley was a Biology major at Simmons. “I explored a lot of options before going to graduate school, to find what was satisfying,” she recalls. “I wasn’t great at being isolated in a lab. I thrived at teaching and interaction, so I knew that I needed a clinical job rather than a research job. I took a job at Beth Israel, thinking I would get experience and then apply to medical school. I absolutely loved it, it was a perfect fit for me.”

While the medical field is always changing, Riley feels that Simmons instilled an excellent grounding in science and the physiology of the body, in addition to teamwork. “Simmons taught me collaborative learning. We were working together to solve problems.” This directly related to her work in hospitals, and later in Rwanda. “No one person cures a patient. [It requires] that ability to work in a group toward a common goal. I think that’s the kind of ethic that Simmons fostered in my education. It was invaluable, though the specifics [of my career] were unknown to me at the time. [Later], as I learned to coach and teach, I learned the purpose of education. I had a great background from Simmons.”

Photos courtesy of Marilyn Riley